December 2021

Ventilation and use of CO2 sensors in the community

Since summer 2020, the municipality of Kraainem has been making CO2 sensors available to shopkeepers, public places, churches, associations …. Since September 2021, large CO2 sensors have also been installed in the sports hall, the school refectory, the Agora hall, etc. As winter approaches, more and more people will be gathering indoors, and regular ventilation is an absolute necessity to limit the spread of the Coronavirus.

Summer 2020 – March 2021

Under normal conditions,

– We breathe 450 l of air per hour, or 10.8 m3 per 24 h, or 13 kg…

– We emit 18 l of CO2 per person per hour

– The concentration [CO2] in the outside air is 400 ppm (parts per million), or 0.04%.

– The air we breathe out has a concentration [CO2] of 40,000 ppm, or 4%.

– So we breathe in air at min 400 ppm, and exhale it at 40,000 ppm.

– There are several hundred potential pollutants in a building (paint, glue, furniture, etc.), and it’s impossible to measure them all. On the other hand, you can ventilate and use CO2 as a marker.

– In the case of COVID, it is assumed that aerosols are a major source of contamination. A contagious person will emit contaminating aerosols, as well as CO2 when breathing. If we limit CO2, we limit the risks.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the medical profession in general, good ventilation of indoor spaces is one of the preventive measures that can limit the spread of COVID-19 via aerosols. As a result, since summer 2020, the Kraainem municipality has been providing CO2 sensors (*) free of charge for publicly accessible areas. The use of these devices makes it possible to determine when additional ventilation with outside air is required, for example by opening windows and doors. By the beginning of March 2021, we had distributed over 170 collectors in the Commune to restaurants, cafés, communal buildings, police offices, stores, doctors’ surgeries, physiotherapy rooms, hairdressers,…

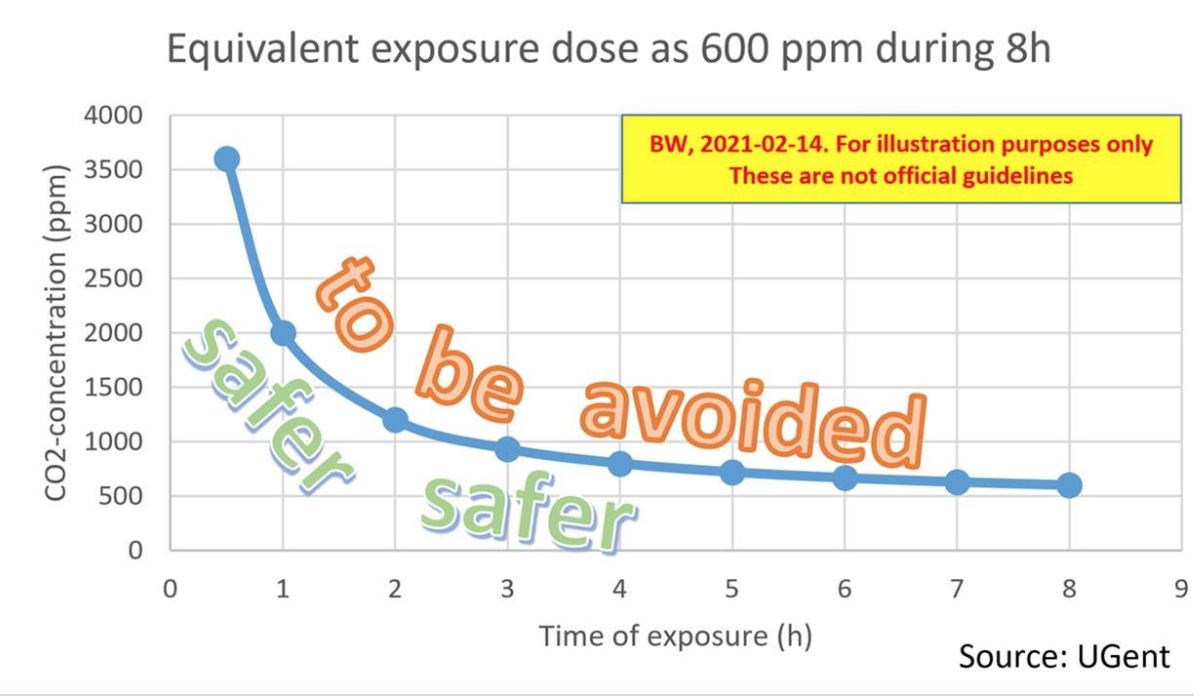

(*) The unit indicates CO2 concentration (in ppm, “parts per million”, 1% = 10,000 ppm) and also gives basic indications via indicator lights. The lower the values, the better (outdoor CO2 concentration is estimated at around 400 ppm). The question is, of course, what is the “safe” level of CO2, and for how long? There is no clear answer to this question at present (**). The reason for this is that it’s hard to say today what dose (= concentration x exposure duration, see graph below) of aerosols becomes dangerous, and so nobody can give a limit (concentration or duration) below which the aerosol situation is 100% safe.

For the time being, therefore, we have to limit ourselves to the ventilation RA for non-residential buildings [Nouvelles règles pour la qualité de l’air intérieur dans les locaux de travail – Service public fédéral Emploi, Travail et Concertation sociale (belgique.be)], which is in fact 900 ppm for most buildings. With an orange light from 800 ppm for our CO2 sensor, we do a little better, but this is certainly no guarantee of 0 risk.

Graph: Dose = concentration x exposure time [on utilise le CO2 comme marqueur d’une concentration potentielle en virus]: one hour at 2000 ppm is equivalent in terms of “dose” to 8 hours at 600 ppm (assuming an outdoor concentration of 400 ppm). No one knows today whether 600 ppm for 8 hours is “safe”, and there are indications that even 500 ppm may not be sufficient (***)…. For the record, this graph was drawn up following several exchanges I had with former colleagues (CTSC and Ghent University) with whom I spent several years working on the new version of the Ventilation AR when I was working as an Energy Advisor for the Confédération de la Construction before becoming Mayor of Kraainem.

(**) Things get complicated as soon as we try to define a limit to be respected to obtain a “safe” situation under current conditions. What are we talking about: what kind of variant, what exposure time, whether or not the mask is worn, the type of activity, etc.? All sorts of parameters that can obviously play an important role. Ideally, we’d like to be able to propose the above type of graph to managers and people in charge of buildings accessible to the public, the level of the curve depending on the sector of activity considered, as well as other parameters mentioned above.

(***) Professor Jimenez of the University of Colorado, with whom we are in regular contact, recommends staying below 700 ppm initially, but also says that even at 500 ppm, he cannot guarantee 0 risk. On the other hand, in schools, for example, it is better to aim for 700 ppm by opening windows as often as possible, rather than the 3000 ppm typically found in many establishments…. So, for the time being at least, we’ll have to confine ourselves to noting that, if we stay within the green zone of the sensor (which turns orange at 800 ppm), ventilation is “better” than what the legislation prescribes (900 ppm).

Next steps?

Once we accept a residual risk, we could of course envisage a whole range of activities being reopened for the long term, provided they are strictly regulated by a strict protocol. This is the subject of Professor Clumeck’s carte blanche (among others) published in Le Soir on 2021-04-12, which advocates a “covid safe” label. Other labels of the same kind are proposed, and are also aimed at reopening certain activities and/or establishments under good safety conditions, rather than making decisions for entire sectors without any distinction between those that can ensure the required level of safety and others.

There probably won’t be a miracle solution in the immediate future, and all contributions are welcome. Opening windows and doors doesn’t pose any particular problems in summer, but as soon as temperatures drop, it’s a different matter. This is when air filtration and/or purification systems can make sense, provided there is a medical green light [condition sine qua non à mon sens avant de pouvoir envisager une quelconque installation au niveau d’une commune].

The “covid safe” label is undoubtedly one piece of the puzzle, but it needs to be well thought out to avoid chaotic situations, discussions and conflicts of all kinds.

In Professor Clumeck’s carte blanche, it is mentioned that local authorities could be given the responsibility of advising, supporting and verifying the “covid safe” compliance of public places. This is a fundamental aspect, because the best system won’t have much effect if it isn’t monitored and/or followed up.